Honey: The Sticky TruthYour Attractive Heading

It’s still mostly fructose.

As I mentioned in my lecture on the realities of food addiction, I am often asked whether honey, a common staple in contemporary Paleo Diets, is beneficial.

Typically I recommend a diet low in sugar to most clients, because of the addictive and rewarding properties of the substance.

1

This means honey, which is mostly sugar,2 typically gets the “thumbs down” as well.

Honey is about 40% fructose, 200% sweeter than glucose, which is found in less sweet carbohydrate sources, and can be used by every cell in your body for energy.3

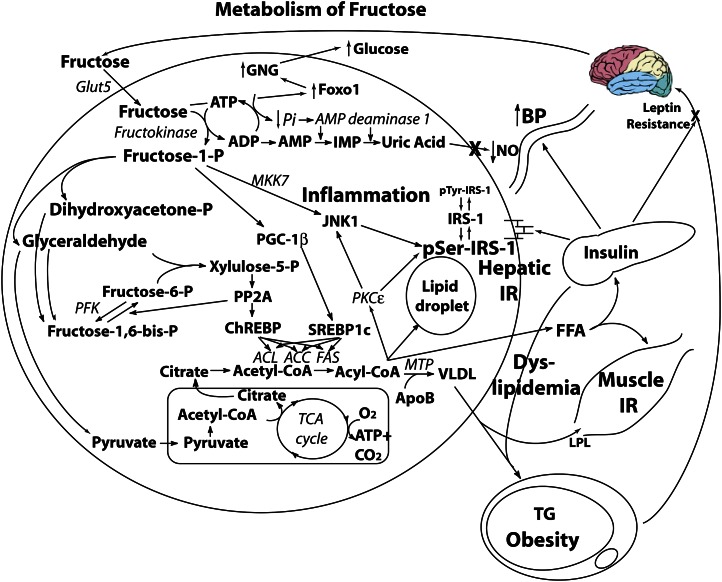

This is in contrast to fructose, which largely gets handled by the GLUT5 transporter, and is almost entirely cleared in the liver.

Fructose does not raise insulin levels,5 reduces leptin (your satiety hormone)6 and has many parallels with ethanol (alcohol).7

With honey being the food single-handedly highest in fructose, only behind soda and applesauce,8 it is generally a good idea to limit intake in today’s modern obesogenic environment.9

However, hunter-gatherers have traditionally sought out honey,10 often enduring great risks to procure the substance.11

While researchers state honey is the most energy-dense food in nature,12, carbohydrates and protein contain 4.1 kcal/gm, Fats (acylglycerols) ~ 8.8 kcal/gm depending upon the acyl group, and ethanol 6.9 kcal/gm.

Accordingly, honey contains almost carbohydrates entirely and, therefore, has a caloric density of roughly half that of fats.

Hence, honey is not the most energy-dense food in nature, but rather fat.

Hunter-gatherers acquired fat (triacylglycerols) from both plant and animal food sources. Concentrated animal triacylglycerol sources include marrow, subcutaneous fat, perinephral fat, mesenteric fat, and retro-orbital fat.

Brain, a highly favored food does not contain triacylglycerols but rather is a rich source of fatty acids contained in the phospholipid fraction and, therefore, remains more energetically dense than carbohydrates. Certain plant foods including nuts, some seeds, olives, and avocadoes are rich sources of monounsaturated fatty acids.

But, honey was a favored food of hunter-gatherers. The Hadza of Tanzania rank honey as their favorite food.13

Also of note, is a study barely a week and a half old, which describes diet-dependent gene expression in honey bees.14 This study details the gene expression, which vastly differs between bees fed honey, and those fed either sucrose or high fructose corn syrup (HFCS).

This study points out key differences in the gene expression effects of a natural food like honey, compared to man-made creations.

Since it was traditionally thought that bees would respond equally to table sugar and HFCS, as they would to honey, this study is of vast importance, showing the differential responses, genetically, that bees exhibit. This has potential translational implications for humans,15 which is vital in the obesity pandemic,16 and the metabolically diseased state,17 in which we currently live.

Could a simple replacement of natural sweeteners, like honey, with man-made creations, like HFCS, be a potential cause of genetic changes?18

It seems possible. However, we must proceed with caution, and never base any substantial conclusions on one study, especially when it was not performed on human beings.

This study is also supported by another recent finding that HFCS-rich diets may be partially to blame for collapsing bee colonies.19

Interestingly, some studies have shown honey may instead have potentially “obesity-protective” effects.20

This is based on observations in responses to the hormone ghrelin and peptide YY (3-36).21 In another study, researchers showed that honey has a gentler effect on blood sugar levels on a per-gram basis, at least when compared with sucrose.22

However, to me, this doesn’t change the biochemistry of fructose, of which honey is largely comprised. It makes more sense to eat whole fruit, starchy sources of carbohydrates, and vegetables.

It is true that the metabolism and neurochemical responses of pure fructose, such as those used in many studies, may be slightly different than the fructose found in honey.

But, in practice, humans consume sweet foods with complete abandon,23 whether it’s man-made or natural.24

Keep honey as a rare treat, as our hunter-gatherer ancestors (seasonally) did.25 This will limit reward to your brain, which will help to limit more reward-seeking behaviors.26

Casey Thaler, B.A., NASM-CPT, FNS

Casey Thaler, B.A., NASM-CPT, FNS is an NASM® certified personal trainer and NASM® certified fitness nutrition specialist. He writes for Paleo Magazine® and for PaleoHacks. He also runs his own nutrition and fitness consulting company, Eat Clean, Train Clean®. He is pursuing his Ph.D in Nutritional Biochemistry, hopefully from Harvard University.

References

1. Lustig RH. Fructose: it’s “alcohol without the buzz”. Adv Nutr. 2013;4(2):226-35.

2. Available at: http://nutritiondata.self.com/facts/sweets/5568/2. Accessed July 23, 2014.

3. Petelinc T, Polak T, Jamnik P. Insight into the molecular mechanisms of propolis activity using a subcellular proteomic approach. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(47):11502-10.

4. Tappy L, Lê KA. Metabolic effects of fructose and the worldwide increase in obesity. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(1):23-46.

5. Schaefer EJ, Gleason JA, Dansinger ML. Dietary fructose and glucose differentially affect lipid and glucose homeostasis. J Nutr. 2009;139(6):1257S-1262S.

6. Shapiro A, Mu W, Roncal C, Cheng KY, Johnson RJ, Scarpace PJ. Fructose-induced leptin resistance exacerbates weight gain in response to subsequent high-fat feeding. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295(5):R1370-5.

7. Lustig RH. Fructose: metabolic, hedonic, and societal parallels with ethanol. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(9):1307-21.

8. Available at: http://nutritiondata.self.com/foods-000011000000000000000.html. Accessed April 12, 2014.

9. Bray GA. How bad is fructose?. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(4):895-6.

10. Douard V, Ferraris RP. Regulation of the fructose transporter GLUT5 in health and disease. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295(2):E227-37.

11. Marlowe FW, Berbesque JC, Wood B, Crittenden A, Porter C, Mabulla A. Honey, Hadza, hunter-gatherers, and human evolution. J Hum Evol. 2014;71:119-28.

12. Eteraf-oskouei T, Najafi M. Traditional and modern uses of natural honey in human diseases: a review. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2013;16(6):731-42.

13. Available at: http://www.epjournal.net/articles/sex-differences-in-food-preferences-of-hadza-hunter-gatherers/. Accessed July 23, 2014.

14. Diet-dependent gene expression in honey bees: honey vs. sucrose or high fructose corn syrup. Scientific Reports. 2014;4

15. Purnell JQ, Klopfenstein BA, Stevens AA, et al. Brain functional magnetic resonance imaging response to glucose and fructose infusions in humans. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(3):229-34.

16. Swinburn BA, Sacks G, Hall KD, et al. The global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804-14.

17. Owens S, Galloway R. Childhood obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2014;16(9):436.

18. Brown RJ, De banate MA, Rother KI. Artificial sweeteners: a systematic review of metabolic effects in youth. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5(4):305-12.

19. Mao W, Schuler MA, Berenbaum MR. Honey constituents up-regulate detoxification and immunity genes in the western honey bee Apis mellifera. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(22):8842-6.

20. Erejuwa OO, Sulaiman SA, Wahab MS. Honey–a novel antidiabetic agent. Int J Biol Sci. 2012;8(6):913-34.

21. Larson-meyer DE, Willis KS, Willis LM, et al. Effect of honey versus sucrose on appetite, appetite-regulating hormones, and postmeal thermogenesis. J Am Coll Nutr. 2010;29(5):482-93.

22. Shambaugh P, Worthington V, Herbert JH. Differential effects of honey, sucrose, and fructose on blood sugar levels. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1990;13(6):322-5.

23. Bray GA. Fructose: should we worry? Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32 Suppl 7:S127-31.

24. Avena NM, Rada P, Hoebel BG. Evidence for sugar addiction: behavioral and neurochemical effects of intermittent, excessive sugar intake. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;32(1):20-39.

25. Pontzer H, Raichlen DA, Wood BM, Mabulla AZ, Racette SB, Marlowe FW. Hunter-gatherer energetics and human obesity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7):e40503.

26. Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Tomasi D, Baler R. Food and drug reward: overlapping circuits in human obesity and addiction. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2012;11:1-24.